Beschrijving

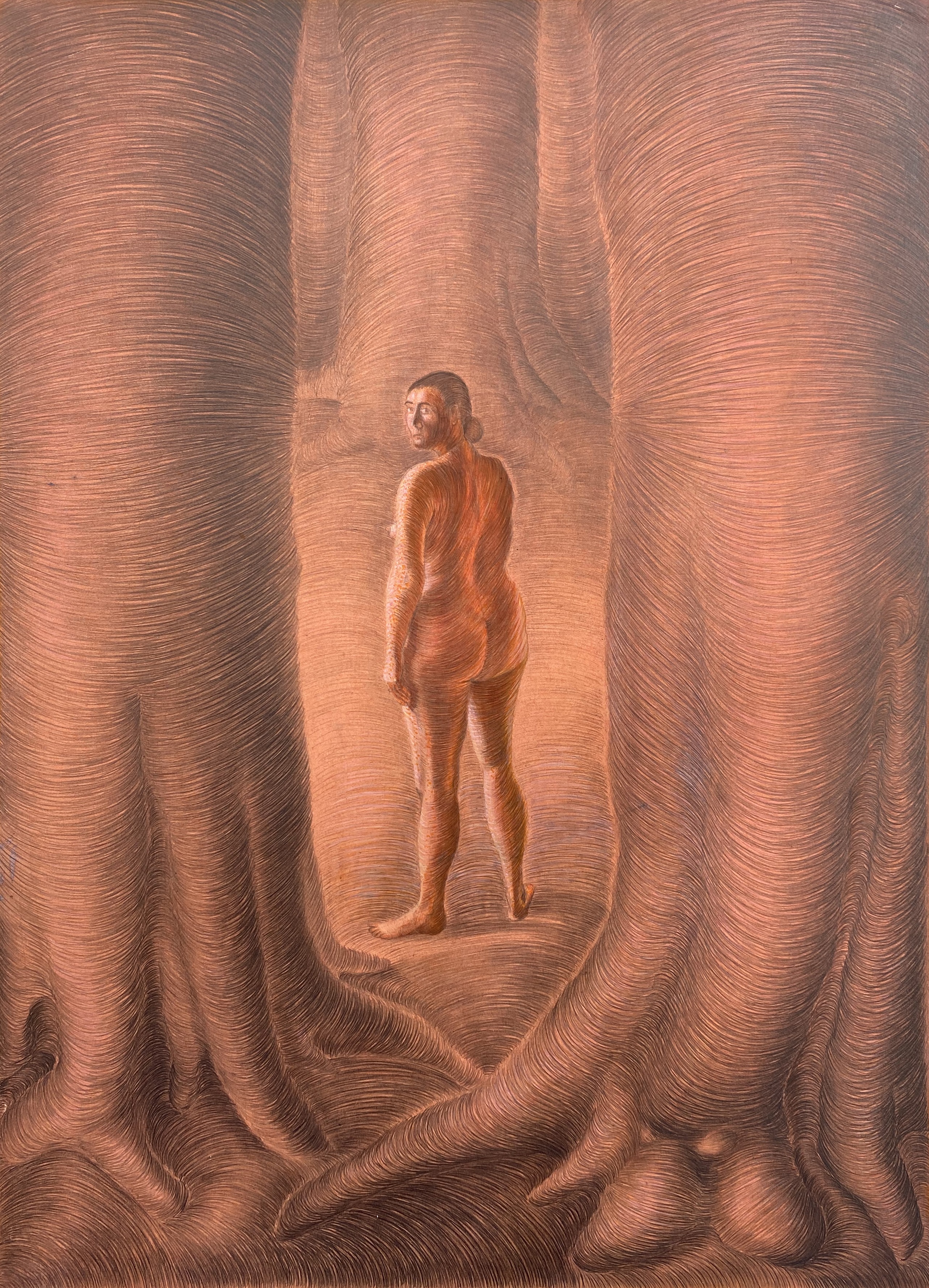

A series of 9 herbaria (one with gouache and pencil), signed 'Sjoerd Buisman' (on the 9th piece); all with the artist's stamp and numbered 1 through 9 (on the reverse), all framed separately, each 165x42,5 cm (incl. the artist's frame) Executed in 1978.

Provenance:

Property from the Chateau Collection Sjoerd Buisman.

Literature:

-W. van den Belt, ‘Sjoerd Buisman. de bomen van Buisman’, Zwolle 2015, pp. 30/31 illustrated in colour.

-K. de Boer, ‘Sjoerd Buisman. Groeiwerken 1987-1997’, Amsterdam, 1998, p. 94, illustrated in black and white.

Exhibited:

-Oxford, Museum of Modern Art, 1980.

-Cologne, Baukunst Galerie, 'Manipulations', 23 Sept. - 6 Oct. 2006.

-Bunnik, Museum Oud Amelisweerd, 'Natura Artis Magistra', 11 April - 29 Sept. 2015.

“Sjoerd Buisman is not a biologist, but an artist,” so reads the message in an article on Buisman’s website. Nature and art, art and nature, which one comes first in Buisman’s work, and how are they linked? It is sometimes hard to see the boundaries between one and the other; nature fuses with art and the other way round. In the beginning of Buisman’s career nature always seems to be subordinate to the manipulations of the human hand. All the shaping, pushing, controlling of leaves, roots and branches is for the sake of art. He observes, registers and then builds his own artistically shaped nature. His initial photographs and notes reveal not only the magic and power of nature but also the inventiveness of men and above all the sharp eye of the artist.

Later on in his career, Buisman’s focus seems to have shifted, from manipulating the plant into art, to just observing the way nature creates nature, to creating art along the lines of natural forms, especially of spiral shapes. Beautiful objects, into which the graceful shapes of nature have found their way, are the result. Buisman’s keen eye, able hands and deep knowledge of materials have earned him a rock-solid place in post-war Dutch art.

Ever since Buisman was a young man, he had an acute interest in plants and their growth process. This interest was incorporated into his early artwork from the late 1960’s, at which time he was also greatly influenced by conceptual art and the Arte Povera movement. Potatoes, seeds, fruit and leaves became part of his experiments in which he researched how invisible qualities like gravity, light and moisture could influence natural objects. In his ‘Etiolation’ projects for instance, he meticulously documented, with the help of pictures, the dying process of plants that had been blocked from any daylight during their growing process. The whole process of the growing shoots looking for light, winding themselves into weird shapes to finally end up in slimy threads, was documented to become a form of art.

The reactions to Buisman’s ‘plant art’ were divided: he received both loud applause as well as some quite severe criticism, as was to be expected. However, by the end of the 1970’s, his breakthrough as an artist was firmly established and his work became part of many exhibitions in the Netherlands as well as abroad. Buisman took the criticism in his stride, considering it as part of a world that was not yet ready for his message. “I had an ideal at that time. I wanted to change the way people looked at things, not only at nature, but also at art. I connected – as a credo – nature with culture, as being one of a kind. I still want to do this, but nowadays these things are accepted.”

In the mid 1970’s Buisman took his experiments one step further by not only registering the growing processes, but by actually giving them form. Just like with the Land Art artists Hamish Fulton and Robert Smithson, nature becomes the material art is made of. He plants palisades of birch, willow and spruce in rectangles or in long lines along rivers, on the edge of ponds and in meadows. In 1984, together with the British sculptor David Nash, he was commissioned by the Kröller-Müller Museum for a project called “Planting Pieces”: it included a Birch Mountain and a Birch palisade.

Buisman’s interest in nature and plants, took him to countries like the Canary Islands, Venezuela, Indonesia and the Philippines where he searched the jungle for his favourite forms. It is during one of these trips that he discovers symmetrical patterns in banana leaves, caused by insects. The rhythm of the pattern being the result of the fact that the leaves were initially rolled up. Apart from just observing them for what they are: banana leaves gnawed on by insects, Buisman put them in separate frames (herbaria) which, together with the gouache and notes in pencil, resulted in a stunning series (Lot 19). With this he again confirms the idea that art can be found in nature, but that it takes the artist and his artistic outlook on how to exhibit his ‘trouvaille’ to make nature into art.

It is during that same period that he comes across the spiral form. “I sowed a banana plant and when it started to grow, I accidentally noticed that the leaf lobes were spirally attached to the stem. I found that really wonderful. The spiral is the most important growth structure that we know. You can see it in the double screw arrangement of the DNA molecule and it is also the most important ordering principle in plants.” In the beginning of the 1980’s his research was followed by the spiral-formed paper mache statues. Not long after that his well-known concept of the ‘Phyllotaxis’ followed.

Buisman has been developing his nature-inspired art ever since. Still searching for beautiful forms, still trying to pass along the magic spell of nature, he progresses into an even further field where art and nature merge into one awe-inspiring experience. “The characteristic of a spiral is that it turns back in a similar way towards the place from which it came. It just stretches out a little further. That's how I want to develop myself.”

Literature

Ik zaaide een banaan en zag de bladlobben in spiralen groeien / Lucette ter Borg, NRC, 07-03-1992

Sjoerd Buisman : Groeiwerken 1967-1997, 1998, passim

Sjoerd Buisman, in de tuin van de kunst / Cherry Duyns, Cees de Boer, 2013, passim

De Bomen van Buisman / Werner van den Belt, 2015, passim

Details

- Databanknummer:

- 91867

- Lotnummer:

- -

- Advertentietype

- Archief

- Instelling:

- Venduehuis Den Haag

- Veilingdatum:

- -

- Veilingnummer:

- -

- Stad

- -

- Limietprijs

- -

- Aankoopprijs

- -

- Verkoopprijs

- -

- Hamerprijs

- -

- Status

- Niet verkocht

Technische details

- Kunstvorm:

- Collage- Compositie- en Mozaiekkunst

- Technieken:

- Gouache, Potlood, Beeldhouwkunst en kunstobjekten

- Dragers:

- Hout, Plantaardige vezels

- Lengte:

- 165 cm

- Breedte:

- 42.5 cm

- Hoogte:

- -

- Oplage:

- -

Beschrijving

A series of 9 herbaria (one with gouache and pencil), signed 'Sjoerd Buisman' (on the 9th piece); all with the artist's stamp and numbered 1 through 9 (on the reverse), all framed separately, each 165x42,5 cm (incl. the artist's frame) Executed in 1978.

Provenance:

Property from the Chateau Collection Sjoerd Buisman.

Literature:

-W. van den Belt, ‘Sjoerd Buisman. de bomen van Buisman’, Zwolle 2015, pp. 30/31 illustrated in colour.

-K. de Boer, ‘Sjoerd Buisman. Groeiwerken 1987-1997’, Amsterdam, 1998, p. 94, illustrated in black and white.

Exhibited:

-Oxford, Museum of Modern Art, 1980.

-Cologne, Baukunst Galerie, 'Manipulations', 23 Sept. - 6 Oct. 2006.

-Bunnik, Museum Oud Amelisweerd, 'Natura Artis Magistra', 11 April - 29 Sept. 2015.

“Sjoerd Buisman is not a biologist, but an artist,” so reads the message in an article on Buisman’s website. Nature and art, art and nature, which one comes first in Buisman’s work, and how are they linked? It is sometimes hard to see the boundaries between one and the other; nature fuses with art and the other way round. In the beginning of Buisman’s career nature always seems to be subordinate to the manipulations of the human hand. All the shaping, pushing, controlling of leaves, roots and branches is for the sake of art. He observes, registers and then builds his own artistically shaped nature. His initial photographs and notes reveal not only the magic and power of nature but also the inventiveness of men and above all the sharp eye of the artist.

Later on in his career, Buisman’s focus seems to have shifted, from manipulating the plant into art, to just observing the way nature creates nature, to creating art along the lines of natural forms, especially of spiral shapes. Beautiful objects, into which the graceful shapes of nature have found their way, are the result. Buisman’s keen eye, able hands and deep knowledge of materials have earned him a rock-solid place in post-war Dutch art.

Ever since Buisman was a young man, he had an acute interest in plants and their growth process. This interest was incorporated into his early artwork from the late 1960’s, at which time he was also greatly influenced by conceptual art and the Arte Povera movement. Potatoes, seeds, fruit and leaves became part of his experiments in which he researched how invisible qualities like gravity, light and moisture could influence natural objects. In his ‘Etiolation’ projects for instance, he meticulously documented, with the help of pictures, the dying process of plants that had been blocked from any daylight during their growing process. The whole process of the growing shoots looking for light, winding themselves into weird shapes to finally end up in slimy threads, was documented to become a form of art.

The reactions to Buisman’s ‘plant art’ were divided: he received both loud applause as well as some quite severe criticism, as was to be expected. However, by the end of the 1970’s, his breakthrough as an artist was firmly established and his work became part of many exhibitions in the Netherlands as well as abroad. Buisman took the criticism in his stride, considering it as part of a world that was not yet ready for his message. “I had an ideal at that time. I wanted to change the way people looked at things, not only at nature, but also at art. I connected – as a credo – nature with culture, as being one of a kind. I still want to do this, but nowadays these things are accepted.”

In the mid 1970’s Buisman took his experiments one step further by not only registering the growing processes, but by actually giving them form. Just like with the Land Art artists Hamish Fulton and Robert Smithson, nature becomes the material art is made of. He plants palisades of birch, willow and spruce in rectangles or in long lines along rivers, on the edge of ponds and in meadows. In 1984, together with the British sculptor David Nash, he was commissioned by the Kröller-Müller Museum for a project called “Planting Pieces”: it included a Birch Mountain and a Birch palisade.

Buisman’s interest in nature and plants, took him to countries like the Canary Islands, Venezuela, Indonesia and the Philippines where he searched the jungle for his favourite forms. It is during one of these trips that he discovers symmetrical patterns in banana leaves, caused by insects. The rhythm of the pattern being the result of the fact that the leaves were initially rolled up. Apart from just observing them for what they are: banana leaves gnawed on by insects, Buisman put them in separate frames (herbaria) which, together with the gouache and notes in pencil, resulted in a stunning series (Lot 19). With this he again confirms the idea that art can be found in nature, but that it takes the artist and his artistic outlook on how to exhibit his ‘trouvaille’ to make nature into art.

It is during that same period that he comes across the spiral form. “I sowed a banana plant and when it started to grow, I accidentally noticed that the leaf lobes were spirally attached to the stem. I found that really wonderful. The spiral is the most important growth structure that we know. You can see it in the double screw arrangement of the DNA molecule and it is also the most important ordering principle in plants.” In the beginning of the 1980’s his research was followed by the spiral-formed paper mache statues. Not long after that his well-known concept of the ‘Phyllotaxis’ followed.

Buisman has been developing his nature-inspired art ever since. Still searching for beautiful forms, still trying to pass along the magic spell of nature, he progresses into an even further field where art and nature merge into one awe-inspiring experience. “The characteristic of a spiral is that it turns back in a similar way towards the place from which it came. It just stretches out a little further. That's how I want to develop myself.”

Literature

Ik zaaide een banaan en zag de bladlobben in spiralen groeien / Lucette ter Borg, NRC, 07-03-1992

Sjoerd Buisman : Groeiwerken 1967-1997, 1998, passim

Sjoerd Buisman, in de tuin van de kunst / Cherry Duyns, Cees de Boer, 2013, passim

De Bomen van Buisman / Werner van den Belt, 2015, passim

Geen prijsinformatie? Sluit een abonnement af.

Aangeboden kunst

Een selectie uit ons kunstaanbod